HIP Health Library

When Hip Replacement is Recommended?

There are several reasons why your doctor may recommend hip replacement surgery. People who benefit from hip replacement surgery often have:

Hip pain that limits everyday activities, such as walking or bending

Hip pain that continues while resting, either day or night

Stiffness in a hip that limits the ability to move or lift the leg

Inadequate pain relief from anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, or walking supports

HIP DISLOCATION

-

Hip Dislocation

Hip Dislocation

This article addresses hip dislocation that results from a traumatic injury. To learn about pediatric developmental hip dislocation, please read Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the Hip (DDH). To learn about dislocation after total hip replacement, please read Total Hip Replacement.

A traumatic hip dislocation occurs when the head of the thighbone (femur) is forced out of its socket in the hip bone (pelvis). It typically takes a major force to dislocate the hip. Car collisions and falls from significant heights are common causes and, as a result, other injuries like broken bones often occur with the dislocation.

A hip dislocation is a serious medical emergency. Immediate treatment is necessary.

-

Anatomy

Anatomy

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

A smooth tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and the socket. It creates a low friction surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other.

The acetabulum is ringed by strong fibrocartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, creating a tight seal and helping to provide stability to the joint.

-

Description

Description

When there is a hip dislocation, the femoral head is pushed either backward out of the socket, or forward.

- Posterior dislocation. In approximately 90% of hip dislocation patients, the thighbone is pushed out of the socket in a backwards direction. This is called a posterior dislocation. A posterior dislocation leaves the lower leg in a fixed position, with the knee and foot rotated in toward the middle of the body.

- Anterior dislocation. When the thighbone slips out of its socket in a forward direction, the hip will be bent only slightly, and the leg will rotate out and away from the middle of the body.

When the hip dislocates, the ligaments, labrum, muscles, and other soft tissues holding the bones in place are often damaged, as well. The nerves around the hip may also be injured.

-

Symptoms & Cause

Symptoms

A hip dislocation is very painful. Patients are unable to move the leg and, if there is nerve damage, may not have any feeling in the foot or ankle area.

Cause

Motor vehicle collisions are the most common cause of traumatic hip dislocations. The dislocation often occurs when the knee hits the dashboard in a collision. This force drives the thigh backwards, which drives the ball head of the femur out of the hip socket. Wearing a seatbelt can greatly reduce your risk of hip dislocation during a collision.

A fall from a significant height (such as from a ladder) or an industrial accident can also generate enough force to dislocate a hip.

With hip dislocations, there are often other related injuries, such as fractures in the pelvis and legs, and back, abdominal, knee, and head injuries. Perhaps the most common fracture occurs when the head of the femur hits and breaks off the back part of the hip socket during the injury. This is called a posterior wall acetabular fracture-dislocation.

-

Doctor Examination

Doctor Examination

A hip dislocation is a medical emergency. Call for help immediately. Do not try to move the injured person, but keep him or her warm with blankets.

In cases in which hip dislocation is the only injury, an orthopaedic surgeon can often diagnose it simply by looking at the position of the leg. Because hip dislocations often occur with additional injuries, your doctor will complete a thorough physical evaluation.

Your doctor may order imaging tests, such as x-rays, to show the exact position of the dislocated bones, as well as any additional fractures in the hip or thighbone.

-

Reduction Procedures

Reduction Procedures

If there are no other injuries, the doctor will administer an anesthetic or a sedative and manipulate the bones back into their proper position. This is called a reduction.

In some cases, the reduction must be done in the operating room with anesthesia. In rare cases, torn soft tissues or small bony fragments block the bone from going back into the socket. When this occurs, surgery is required to remove the loose tissues and correctly position the bones.

Following reduction, the surgeon will request another set of x-rays and possibly a computed tomography (CT) scan to make sure that the bones are in the proper position.

OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP

-

Osteoarthritis of the Hip

Osteoarthritis of the Hip

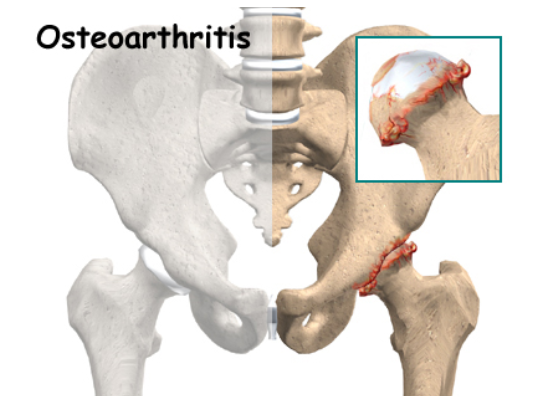

Sometimes called «wear-and-tear» arthritis, osteoarthritis is a common condition that many people develop during middle age or older. In 2011, more than 28 million people in the United States were estimated to have osteoarthritis. It can occur in any joint in the body, but most often develops in weight-bearing joints, such as the hip.

Osteoarthritis of the hip causes pain and stiffness. It can make it hard to do everyday activities like bending over to tie a shoe, rising from a chair, or taking a short walk.

Because osteoarthritis gradually worsens over time, the sooner you start treatment, the more likely it is that you can lessen its impact on your life. Although there is no cure for osteoarthritis, there are many treatment options to help you manage pain and stay active.

-

Anatomy

Anatomy

The hip is one of the body’s largest joints. It is a «ball-and-socket» joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

The bone surfaces of the ball and socket are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth, slippery substance that protects and cushions the bones and enables them to move easily.

The surface of the joint is covered by a thin lining called the synovium. In a healthy hip, the synovium produces a small amount of fluid that lubricates the cartilage and aids in movement.

-

Description

Description

Osteoarthritis is a degenerative type of arthritis that occurs most often in people 50 years of age and older, though it may occur in younger people, too.

In osteoarthritis, the cartilage in the hip joint gradually wears away over time. As the cartilage wears away, it becomes frayed and rough, and the protective joint space between the bones decreases. This can result in bone rubbing on bone. To make up for the lost cartilage, the damaged bones may start to grow outward and form bone spurs (osteophytes).

Osteoarthritis develops slowly and the pain it causes worsens over time.

-

Cause

Cause

Osteoarthritis has no single specific cause, but there are certain factors that may make you more likely to develop the disease, including:

- Increasing age

- Family history of osteoarthritis

- Previous injury to the hip joint

- Obesity

- Improper formation of the hip joint at birth, a condition known as developmental dysplasia of the hip

Even if you do not have any of the risk factors listed above, you can still develop osteoarthritis.

-

Symptoms

Symptoms

The most common symptom of hip osteoarthritis is pain around the hip joint. Usually, the pain develops slowly and worsens over time, although sudden onset is also possible. Pain and stiffness may be worse in the morning, or after sitting or resting for a while. Over time, painful symptoms may occur more frequently, including during rest or at night. Additional symptoms may include:

- Pain in your groin or thigh that radiates to your buttocks or your knee

- Pain that flares up with vigorous activity

- Stiffness in the hip joint that makes it difficult to walk or bend

- «Locking» or «sticking» of the joint, and a grinding noise (crepitus) during movement caused by loose fragments of cartilage and other tissue interfering with the smooth motion of the hip

- Decreased range of motion in the hip that affects the ability to walk and may cause a limp

- Increased joint pain with rainy weather

-

Doctor Examination

Doctor Examination

During your appointment, your doctor will talk with you about your symptoms and medical history, conduct a physical examination, and possibly order diagnostic tests, such as x-rays.

Physical Examination

During the physical examination, your doctor will look for:

- Tenderness about the hip

- Range of passive (assisted) and active (self-directed) motion

- Crepitus (a grating sensation inside the joint) with movement

- Pain when pressure is placed on the hip

- Problems with your gait (the way you walk)

- Any signs of injury to the muscles, tendons, and ligaments surrounding the hip

Imaging Tests

X-rays. These imaging tests create detailed pictures of dense structures, like bones. X-rays of an arthritic hip may show a narrowing of the joint space, changes in the bone, and the formation of bone spurs (osteophytes).

ANESTHESIA FOR HIP AND KNEE SURGERY

-

Anesthesia for Hip and Knee Surgery

Anesthesia for Hip and Knee Surgery

Before your joint replacement surgery, your doctor will discuss anesthesia with you. The selection of anesthesia is a major decision that could have a significant impact on your recovery. It deserves careful consideration and discussion with your surgeon and your anesthesiologist.

Several factors must be considered when selecting anesthesia, including:

- Your past experiences and preferences. Have you ever had anesthesia before? Did you have a reaction to the anesthesia? How do other members of your family react to anesthesia?

- Your current health and physical condition. Do you smoke? Are you overweight? Are you being treated for any condition other than your joint replacement?

- Your reactions to medications. Do you have any allergies? Have you ever experienced bad side effects from a drug? What medications, nutritional supplements, vitamins, or herbal remedies are you currently taking?

- The risks involved. Risks vary, depending on your health and selection of anesthesia, but may include breathing difficulties, allergic reactions and nerve injury. Your surgeon and anesthesiologist will discuss specific risks with you.

- Your healthcare team. The skills and preferences of your surgical and anesthesia team play an important role in the selection of anesthesia.

-

Types of Anesthesia

Types of Anesthesia

There are three broad categories of anesthesia: local, regional and general.

Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia numbs only the specific area being treated. The area is numbed with an injection, spray or ointment that only lasts for a short period of time. Patients remain conscious during this type of anesthesia. This technique is reserved for minor procedures. For major surgery, such as hip or knee replacement, local anesthesia may be used to complement the main type of anesthesia that is used.

Regional Anesthesia

Regional anesthesia involves blocking the nerves to a specific area of the body, without affecting your brain or breathing. Because you remain conscious, you will be given sedatives to relax you and put you in a light sleep.

The three types of regional anesthesia used most frequently in joint replacement surgery are spinal blocks, epidural blocks and peripheral nerve blocks.

- Spinal Block. In a spinal block, the anesthesic drug is injected into the fluid surrounding the spinal cord in the lower part of your back. This produces a rapid numbing effect that wears off after several hours.

- Epidural Block. An epidural block uses a catheter inserted in your lower back to deliver local anesthetics over a variable period of time. The epidural block and the spinal block are administered in a very similar location; however, the epidural catheter is placed in a slightly different area around the spine as compared to a spinal block.

- Peripheral Nerve Block. A peripheral nerve block places local anesthetic directly around the major nerves in your thigh, such as the femoral nerve or the sciatic nerve. These blocks numb only the leg that is injected, and do not affect the other leg. One option for a peripheral block is to perform a one-time injection around the nerves in order to numb the leg just long enough for the surgery. Another option for this type of block is to keep a catheter in place, which can deliver continuous local anesthesia around the nerves for up to several days after surgery.

Advantages to regional anesthesia may include less blood loss, less nausea, less drowsiness, improved pain control after surgery, and reduced risk of serious medical complications, such as heart attack or stroke that — although rare — may occur with general anesthesia.

Side effects from regional anesthesia may include headaches, trouble urinating, allergic reactions, and rarely nerve injury.

General Anesthesia

General anesthesia is often used for major surgery, such as a joint replacement. General anesthesia may be selected based on patient, surgeon, or anesthesiologist preference, or if you are unable to receive regional or local anesthesia. Unlike regional and local anesthesia, general anesthesia affects your entire body. It acts on the brain and nervous system and renders you temporarily unconscious.

- Administration. With general anesthesia, the anesthesiologist administers medication through injection or inhalation. The anesthesiologist will also place a breathing tube down your throat and administer oxygen to assist your breathing.

- Risks. As with any anesthesia, there are risks, which may be increased if you already have heart disease, chronic lung conditions, or other serious medical problems.

General anesthesia affects both your heart and breathing rates, and there is a small risk of a serious medical complication, such as heart attack or stroke.

The tube inserted down your throat may give you a sore throat and hoarse voice for a few days.

Headache, nausea, and drowsiness are also common.

-

Pain Relief After Surgery

The goals of postoperative pain management are to minimize discomfort and allow you to move with less pain in order to participate in physical therapy after surgery. The first few days after hip and knee surgery are usually painful. Your doctor will use a combination of oral medications or intravenous medications to help control your pain and keep you comfortable.

Oral Pain Medications

Oral pain medications may include a combination of non-narcotic pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol), nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as ibuprofen or naproxen, or muscle relaxants such as methocarbamol, and opioid-based medications such as hydrocodone, oxycodone, or tramadol. You should use opioids only as directed by your doctor. Although opioids can help relieve pain after surgery, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your surgery.

Intravenous Pain Medications

Intravenous (IV) pain medications such as morphine and hydromorphone (Dilaudid) are generally used to supplement oral pain medication during severe episodes of pain. The advantage of IV pain medications is that they take effect quickly. It is important to use IV pain medications sparingly in order to avoid serious side effects.

Another method of pain control is called «patient-controlled anesthesia» or «PCA.» With PCA, you will be able to control the flow of intravenous medication, within preset limits, as you feel the need for additional relief.

If an epidural or peripheral nerve block was used for your surgery, the epidural or peripheral catheter can be left in place and anesthesia can be continued in the postoperative period to help control pain. You may also have control over the amount of pain medication you receive in these catheters, within preset limits. You will be closely monitored to avoid complications, such as excessive sedation or falls.

The proper use of pain relievers before, during and after your surgery is an extremely important aspect of your treatment. Proper use of pain medication can encourage healing and make your joint replacement a more satisfying experience. Take time to discuss the options with your doctor, and be sure to ask questions about things you do not understand.

OSTEOPOROSIS

-

Osteoporosis

Osteoporosis

This article provides answers to some common questions about osteoporosis.

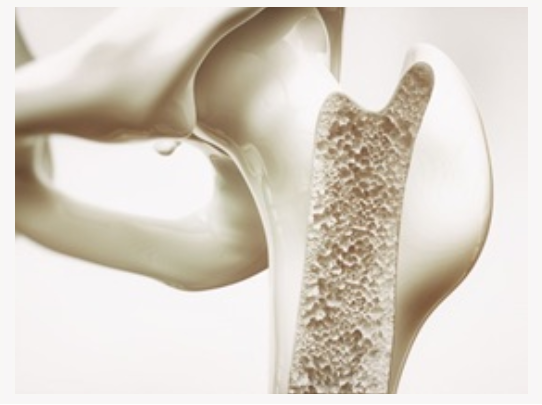

What is osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a disease of progressive bone loss associated with an increased risk of fractures. The term osteoporosis literally means porous bone. The disease often develops unnoticed over many years, with no symptoms or discomfort until a fracture occurs. Osteoporosis often causes a loss of height and dowager’s hump (a severely rounded upper back).

Why should I be concerned about osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is a major health problem, affecting more than 44 million Americans and contributing to an estimated 2 million bone fractures per year. According to the National Osteoporosis Foundation, the number of fractures due to osteoporosis may rise to over 3 million by the year 2025.

One in two women and one in four men older than 50 years will sustain bone fractures caused by osteoporosis. Many of these are painful fractures of the hip, spine, wrist, arm, and leg, which often occur as a result of a fall. However, performing even simple household tasks can result in a fracture of the spine if the bones have been weakened by osteoporosis.

The most serious and debilitating osteoporotic fracture is a hip fracture. Most patients who experience a hip fracture and previously lived independently will require help from their family or home care. All patients who experience a hip fracture will require walking aids for several months, and nearly half will permanently need canes or walkers to move around their house or outdoors. Hip fractures are expensive. Health care costs from hip fractures total more than $11 billion annually, or about $37,000 per patient.

-

What causes osteoporosis?

What causes osteoporosis?

Doctors do not know the exact medical causes of osteoporosis, but they have identified many of the major factors that can lead to the disease.

Aging

Everyone loses bone with age. After 35 years of age, the body builds less new bone to replace the loss of old bone. In general, the older you are, the lower your total bone mass and the greater your risk for osteoporosis.

Heredity

A family history of fractures; a small, slender body build; fair skin; and Caucasian or Asian ethnicity can increase the risk for osteoporosis. Heredity also may help explain why some people develop osteoporosis early in life.

Nutrition and Lifestyle

Poor nutrition, including a low calcium diet, low body weight, and a sedentary lifestyle have been linked to osteoporosis, as have smoking and excessive alcohol use.

Medications and Other Illnesses

Osteoporosis has been linked to the use of some medications, including steroids, and to other illnesses, including some thyroid problems.

-

What can I do to prevent osteoporosis?

What can I do to prevent osteoporosis or keep it from getting worse?

To prevent osteoporosis, slow its progression, and protect yourself from fractures you should include adequate amounts of calcium and Vitamin D in your diet and exercise regularly.

Calcium

During the growing years, your body needs calcium to build strong bones and to create a supply of calcium reserves. Building bone mass when you are young is a good investment for your future. Inadequate calcium during growth can contribute to the development of osteoporosis later in life.

Whatever your age or health status, you need calcium to keep your bones healthy. Calcium continues to be an essential nutrient after growth because the body loses calcium every day. Although calcium cannot prevent gradual bone loss after menopause, it continues to play an essential role in maintaining bone quality. Even if women have gone through menopause or already have osteoporosis, increasing intake of calcium and Vitamin D can decrease the risk of fracture.

How much calcium you need will vary depending on your age and other factors. The National Academy of Sciences makes the following recommendations regarding daily intake of calcium:

- Males and females 9 to 18 years: 1,300 mg per day

- Women and men 19 to 50 years: 1,000 mg per day

- Pregnant or nursing women up to age 18: 1,300 mg per day

- Pregnant or nursing women 19 to 50 years: 1,000 mg per day

- Women and men over 50: 1,200 mg per day

Dairy products, including yogurt and cheese, are excellent sources of calcium. An eight-ounce glass of milk contains about 300 mg of calcium. Other calcium-rich foods include sardines with bones and green leafy vegetables, including broccoli and collard greens.

If your diet does not contain enough calcium, dietary supplements can help. Talk to your doctor before taking a calcium supplement.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D helps your body absorb calcium. The recommendation for Vitamin D is 200-600 IU (international units) daily. Supplemented dairy products are an excellent source of Vitamin D. (A cup of milk contains 100 IU of Vitamin D. A multivitamin contains 400 IU of Vitamin D.) Vitamin supplements can be taken if your diet does not contain enough of this nutrient. Again, consult with your doctor before taking a vitamin supplement. Too much Vitamin D can be toxic.

Exercise Regularly

Like muscles, bones need exercise to stay strong. No matter what your age, exercise can help minimize bone loss while providing many additional health benefits. Doctors believe that a program of moderate, regular exercise (3 to 4 times a week) is effective for the prevention and management of osteoporosis. Weight-bearing exercises such as walking, jogging, hiking, climbing stairs, dancing, treadmill exercises, and weight lifting are probably best. Falls account for 50% of fractures; therefore, even if you have low bone density, you can prevent fractures if you avoid falls. Programs that emphasize balance training, especially tai chi, should be emphasized. Consult with your doctor before beginning any exercise program.

-

How is osteoporosis diagnosed?

How is osteoporosis diagnosed?

The diagnosis of osteoporosis is usually made by your doctor using a combination of a complete medical history and physical examination, skeletal x-rays, bone densitometry, and specialized laboratory tests. If your doctor diagnoses low bone mass, he or she may want to perform additional tests to rule out the possibility of other diseases that can cause bone loss, including osteomalacia (a metabolic bone disease characterized by abnormal mineralization of bone) or hyperparathyroidism (overactivity of the parathyroid glands).

Bone densitometry is a safe, painless x-ray technique that compares your bone density to the peak bone density that someone of your same sex and ethnicity should have reached at 20 to 25 years of age.

Bone densitometry is often performed in women at the time of menopause. Several types of bone densitometry are used today to detect bone loss in different areas of the body. Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA) is one of the most accurate methods, but other techniques can also identify osteoporosis, including single photon absorptiometry (SPA), quantitative computed tomography (QCT), radiographic absorptiometry, and ultrasound. Your doctor can determine which method is best suited for you.

-

How is osteoporosis treated?

How is osteoporosis treated?

Because lost bone cannot be replaced, treatment for osteoporosis focuses on the prevention of further bone loss. Treatment is often a team effort involving a physician or internist, an orthopaedist, a gynecologist, and an endocrinologist.

Although exercise and nutrition therapy are often key components of a treatment plan for osteoporosis, there are other treatments as well.

Estrogen Replacement Therapy

Estrogen replacement therapy (ERT) is often recommended for women at high risk for osteoporosis to prevent bone loss and reduce fracture risk. A measurement of bone density when menopause begins may help you decide whether ERT is right for you. Hormones also prevent heart disease, improve cognitive functioning, and improve urinary function. ERT is not without some risk, including enhanced risk of breast cancer; the risks and benefits of ERT should be discussed with your doctor.

Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators

New anti-estrogens known as SERMs (selective estrogen receptor modulators) can increase bone mass, decrease the risk of spine fractures, and lower the risk of breast cancer.

Calcitonin

Calcitonin is another medication used to decrease bone loss. A nasal spray form of this medication increases bone mass, limits spine fractures, and may offer some pain relief.

Bisphosphonates

Bisphosphonates, including alendronate, markedly increase bone mass and prevent both spine and hip fractures.

ERT, SERMs, calcitonin, and bisphosphonates all offer patient with osteoporosis an opportunity to not only increase bone mass, but also to significantly reduce fracture risk. Prevention is preferable to waiting until treatment is necessary.

Your orthopaedist is a medical doctor with extensive training in the diagnosis and nonsurgical and surgical treatment of the musculoskeletal system, including bones, joints, ligaments, tendons, muscles and nerves. This has been prepared by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons and is intended to contain current information on the subject from recognized authorities. However, it does not represent official policy of the Academy and its text should not be construed as excluding other acceptable viewpoints.

ADOLESCENT HIP DYSPLASIA

-

Hip Dysplasia

The hip is a «ball-and-socket» joint. In a normal hip, the ball at the upper end of the femur (thighbone) fits firmly into the socket, which is a curved portion of the pelvis called the acetabulum. In a young person with hip dysplasia, the hip joint has not developed normally—the acetabulum is too shallow to adequately support and cover the head of the femur. This abnormality can cause a painful hip and the early development of osteoarthritis, a condition in which the articular cartilage in the joint wears away and bone rubs against bone.

Adolescent hip dysplasia is usually the end result of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH), a condition that occurs at birth or in early childhood. Although infants are routinely screened for DDH, some cases remain undetected or are mild enough that they are left untreated. These patients may not show symptoms of hip dysplasia until reaching adolescence.

Treatment for adolescent hip dysplasia focuses on relieving pain while preserving the patient’s natural hip joint for as long as possible. In many cases, this is achieved through surgery to restore the normal anatomy of the joint and delay or prevent the onset of painful osteoarthritis.

-

Anatomy

The hip is one of the body’s largest joints. It is a «ball-and-socket» joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is a part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

The bone surfaces of the ball and socket are covered with articular cartilage, a smooth, slippery substance that protects and cushions the bones and enables them to move easily.

The acetabulum is ringed by strong fibrocartilage called the labrum. The labrum forms a gasket around the socket, creating a tight seal and helping to hold the femoral head in place.

-

Description

In patients with hip dysplasia, the acetabulum is shallow, meaning that the ball, or femoral head, cannot firmly fit into the socket.

As a result of this abnormality, the way that force is normally transmitted between the bone surfaces is altered. The labrum can end up bearing the forces that should normally be distributed evenly throughout the hip joint. In addition, more force is placed on a smaller surface of the hip cartilage and labrum. Over time, the smooth articular cartilage becomes frayed and wears away and the labrum becomes torn or damaged. These degenerative changes can progress to early osteoarthritis.

The severity of hip dysplasia can vary from patient to patient. In mild cases, the head of the femur may simply be loose in the socket. In more severe cases, there may be complete instability in the joint and/or the femoral head may be completely dislocated out of the socket.

-

Cause

Adolescent hip dysplasia usually results from developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) that is undiscovered or untreated during infancy or early childhood.

DDH can occur in families, passed on from one generation to the next. It can be present in either hip and in any individual. It usually affects the left hip and occurs more often in:

Girls

First-born children

Babies born in the breech position -

Symptoms

Hip dysplasia in younger children is not a painful condition. However, over time, pain results when the altered forces in the hip cause degenerative changes to occur in the articular cartilage and the labrum. In most cases, this pain is:

Located in the groin area, although it may sometimes be more toward the outside of the hip

Occasional and mild initially, but may increase in frequency and intensity over time

Worse with activity or near the end of the day

Some patients may also experience the feeling of locking, catching, or popping within the groin. -

Doctor Examination

Physical Examination

During the physical examination, your doctor will discuss your child’s medical history and symptoms. He or she will move your child’s hip in different directions to assess the range of motion and duplicate the pain or discomfort he or she is feeling.Imaging Studies

In most cases, adolescent hip dysplasia can be diagnosed with just a physical exam. Your doctor may order imaging studies, however, to rule out other causes for your child’s pain and to help confirm the diagnosis.X-rays. X-rays provide images of bone, and will help your doctor assess the alignment of the acetabulum and femoral head. An x-ray can also show signs of arthritis.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans. More detailed than a plain x-ray, CT scans can help your doctor determine the severity of dysplasia.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans. These studies can create better images of the body’s soft tissues. An MRI can help your doctor find damage to the labrum and articular cartilage -

Treatment

Treatment for adolescent hip dysplasia focuses on delaying or preventing the onset of osteoarthritis while preserving the natural hip joint for as many years as possible.

Nonsurgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend nonsurgical treatment if your child has mild hip dysplasia and no damage to the labrum or articular cartilage. Nonsurgical treatment may also be tried initially for patients who have such extensive joint damage that the only surgical option would be a total hip replacement.Common nonsurgical treatments for adolescent hip dysplasia include:

Observation. If your child has minimal symptoms and mild dysplasia, your doctor may recommend simply monitoring the condition to make sure it does not get worse. Your child will have follow-up visits every 6 to 12 months so that the doctor can check for any progression that may warrant treatment.

Lifestyle modification. Your doctor may also recommend that your child avoid the activities that cause the pain and discomfort. For a child who is overweight, losing weight will also help to reduce pressure on the hip joint.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises can improve the range of motion in the hip and strengthen the muscles that support the joint. This can relieve some stress on the injured labrum or cartilage.

Medications. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen and naproxen, can help relieve pain and reduce swelling in an arthritic joint. In addition, cortisone is an anti-inflammatory agent that can be injected directly into a joint. Although an injection of cortisone can provide pain relief and reduce inflammation, the effects are temporary.

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your child is experiencing pain and has limited damage to the articular cartilage in his or her hip. The surgical procedure most commonly used to treat hip dysplasia is an osteotomy or «cutting of the bone.» In an osteotomy, the doctor reshapes and reorients the acetabulum and/or femur so that the two joint surfaces are in a more normal position.There are different types of osteotomies that can be performed to treat hip dysplasia. The specific procedure your doctor recommends will depend on a number of factors, including:

- Your child’s age

- The severity of the dysplasia

- The extent of damage to the labrum

- Whether osteoarthritis is present

- The number of remaining growing years

- Periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). Currently, the osteotomy procedure most commonly used to treat adolescent hip dysplasia is a periacetabular osteotomy (PAO). «Periacetabular» means «around the acetabulum.»

In most cases, PAO takes from 2 to 3 hours to perform. During the surgery, the doctor makes four cuts in the pelvic bone around the hip joint to loosen the acetabulum. He or she then rotates the acetabulum, repositioning it into a more normal position over the femoral head. The doctor will use x-rays to direct the bony cuts and to ensure that the acetabulum is repositioned correctly. Once the bone is repositioned, the doctor inserts several small screws to hold it in place until it heals.

Arthroscopy. In conjunction with PAO, your doctor may use hip arthroscopy to repair a torn labrum. During arthroscopy, the doctor inserts a small camera, called an arthroscope, into the joint. The camera displays pictures on a television screen, and your doctor uses these images to guide miniature surgical instruments. Arthroscopic procedures may include:

Labral refixation. In this procedure, the doctor trims the torn and frayed tissue around the acetabular rim and reattaches the torn labrum to the bone of the rim.

Debridement. In some cases, simply removing the torn or weakened labral tissue can provide pain relief.

FEMUR SHAFT FRACTURES (Broken Thighbone)

-

Broken Thighbone

Your thighbone (femur) is the longest and strongest bone in your body. Because the femur is so strong, it usually takes a lot of force to break it. Motor vehicle collisions, for example, are the number one cause of femur fractures.

The long, straight part of the femur is called the femoral shaft. When there is a break anywhere along this length of bone, it is called a femoral shaft fracture. This type of broken leg almost always requires surgery to heal.

-

Types of Femoral Shaft Fractures

Femur fractures vary greatly, depending on the force that causes the break. The pieces of bone may line up correctly (stable fracture) or be out of alignment (displaced fracture). The skin around the fracture may be intact (closed fracture) or the bone may puncture the skin (open fracture).

Doctors describe fractures to each other using classification systems. Femur fractures are classified depending on:

The location of the fracture (the femoral shaft is divided into thirds: distal, middle, proximal)

The pattern of the fracture (for example, the bone can break in different directions, such as crosswise, lengthwise, or in the middle)

Whether the skin and muscle over the bone is torn by the injury

The most common types of femoral shaft fractures include:Transverse fracture. In this type of fracture, the break is a straight horizontal line going across the femoral shaft.

Oblique fracture. This type of fracture has an angled line across the shaft.

Spiral fracture. The fracture line encircles the shaft like the stripes on a candy cane. A twisting force to the thigh causes this type of fracture.

Comminuted fracture. In this type of fracture, the bone has broken into three or more pieces. In most cases, the number of bone fragments corresponds with the amount of force needed to break the bone.

Open fracture. If a bone breaks in such a way that bone fragments stick out through the skin or a wound penetrates down to the broken bone, the fracture is called an open or compound fracture. Open fractures often involve much more damage to the surrounding muscles, tendons, and ligaments. They have a higher risk for complications—especially infections—and take a longer time to heal.

-

Cause

Femoral shaft fractures in young people are frequently due to some type of high-energy collision. The most common cause of femoral shaft fracture is a motor vehicle or motorcycle crash. Being hit by a car while walking is another common cause, as are falls from heights and gunshot wounds.

A lower-force incident, such as a fall from standing, may cause a femoral shaft fracture in an older person who has weaker bones.

-

Symptoms

A femoral shaft fracture usually causes immediate, severe pain. You will not be able to put weight on the injured leg, and it may look deformed—shorter than the other leg and no longer straight.

-

Doctor Examination

Medical History and Physical Examination

It is important that your doctor know the specifics of how you hurt your leg. For example, if you were in a car accident, it would help your doctor to know how fast you were going, whether you were the driver or a passenger, whether you were wearing your seat belt, and if the airbags went off. This information will help your doctor determine how you were hurt and whether you may be hurt somewhere else.It is also important for your doctor to know if you have any other health conditions, such as high blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, or allergies. Your doctor will also ask you if you use tobacco products or are taking any medications.

After discussing your injury and medical history, your doctor will do a careful examination. He or she will assess your overall condition, and then focus on your leg. Your doctor will look for:

- An obvious deformity of the thigh/leg (an unusual angle, twisting, or shortening of the leg)

- Breaks in the skin

- Bruises

- Bony pieces that may be pushing on the skin

- After the visual inspection, your doctor will feel along your thigh, leg, and foot looking for abnormalities and checking the tightness of the skin and muscles around your thigh. He or she will also feel for pulses. If you are awake, your doctor will test for sensation and movement in your leg and foot.

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests will provide your doctor with more information about your injury.X-rays. The most common way to evaluate a fracture is with x-rays, which provide clear images of bone. X-rays can show whether a bone is intact or broken. They can also show the type of fracture and where it is located within the femur.

Computerized tomography (CT) scans. If your doctor still needs more information after reviewing your x-rays, he or she may order a CT scan. A CT scan shows a cross-sectional image of your limb. It can provide your doctor with valuable information about the severity of the fracture. For example, sometimes the fracture lines can be very thin and hard to see on an x-ray. A CT scan can help your doctor see the lines more clearly.

-

Treatment

Nonsurgical Treatment

Most femoral shaft fractures require surgery to heal. It is unusual for femoral shaft fractures to be treated without surgery. Very young children are sometimes treated with a cast.

Surgical Treatment

Timing of surgery. Most femur fractures are fixed within 24 to 48 hours. On occasion, fixation will be delayed until other life-threatening injuries or unstable medical conditions are stabilized. To reduce the risk of infection, open fractures are treated with antibiotics as soon as you arrive at the hospital. The open wound, tissues, and bone will be cleaned during surgery.

For the time between initial emergency care and your surgery, your doctor may place your leg either in a long-leg splint or in traction. This is to keep your broken bones as aligned as possible and to maintain the length of your leg.

Skeletal traction is a pulley system of weights and counterweights that holds the broken pieces of bone together. It keeps your leg straight and often helps to relieve pain.

External fixation. In this type of operation, metal pins or screws are placed into the bone above and below the fracture site. The pins and screws are attached to a bar outside the skin. This device is a stabilizing frame that holds the bones in the proper position.

External fixation is usually a temporary treatment for femur fractures. Because they are easily applied, external fixators are often put on when a patient has multiple injuries and is not yet ready for a longer surgery to fix the fracture. An external fixator provides good, temporary stability until the patient is healthy enough for the final surgery. In some cases, an external fixator is left on until the femur is fully healed, but this is not common.

Intramedullary nailing. Currently, the method most surgeons use for treating femoral shaft fractures is intramedullary nailing. During this procedure, a specially designed metal rod is inserted into the canal of the femur. The rod passes across the fracture to keep it in position.

An intramedullary nail can be inserted into the canal either at the hip or the knee. Screws are placed above and below the fracture to hold the leg in correct alignment while the bone heals.

Intramedullary nails are usually made of titanium. They come in various lengths and diameters to fit most femur bones.

Plates and screws. During this operation, the bone fragments are first repositioned (reduced) into their normal alignment. They are held together with screws and metal plates attached to the outer surface of the bone.

Plates and screws are often used when intramedullary nailing may not be possible, such as for fractures that extend into either the hip or knee joints.

-

Recovery

Most femoral shaft fractures take 3 to 6 months to completely heal. Some take even longer, especially if the fracture was open or broken into several pieces or if the patient uses tobacco products.

Pain Management

Pain after an injury or surgery is a natural part of the healing process. Your doctor and nurses will work to reduce your pain, which can help you recover faster.Medications are often prescribed for short-term pain relief after surgery or an injury. Many types of medications are available to help manage pain. These include acetaminophen, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), gabapentinoids, muscle relaxants, opioids, and topical pain medications. Your doctor may use a combination of these medications to improve pain relief, as well as minimize the need for opioids. Some pain medications may have side effects that can impact your ability to drive and do other activities. Your doctor will talk to you about the side effects of your pain medications.

Be aware that although opioids help relieve pain after surgery or an injury, they are a narcotic and can be addictive. Opioid dependency and overdose has become a critical public health issue in the U.S. It is important to use opioids only as directed by your doctor. As soon as your pain begins to improve, stop taking opioids. Talk to your doctor if your pain has not begun to improve within a few days of your treatment.

Weightbearing

Many doctors encourage leg motion early on in the recovery period. It is very important to follow your doctor’s instructions for putting weight on your injured leg to avoid problems.In some cases, doctors will allow patients to put as much weight as possible on the leg right after surgery. However, you may not be able to put full weight on your leg until the fracture has started to heal. Be sure to follow your doctor’s instructions carefully.

When you begin walking, you will probably need to use crutches or a walker for support.

Physical Therapy

Because you will most likely lose muscle strength in the injured area, exercises during the healing process are important. Physical therapy will help to restore normal muscle strength, joint motion, and flexibility. It can also help you manage your pain after surgery.A physical therapist will most likely begin teaching you specific exercises while you are still in the hospital. The therapist will also help you learn how to use crutches or a walker.

INFLAMMATORY ARTHRITIS OF THE HIP

-

Hip Inflammation

There are more than 100 different forms of arthritis, a disease that can make it difficult to do everyday activities because of joint pain and stiffness.

Inflammatory arthritis occurs when the body’s immune system becomes overactive and attacks healthy tissues. It can affect several joints throughout the body at the same time, as well as many organs, such as the skin, eyes, and heart.

There are three types of inflammatory arthritis that most often cause symptoms in the hip joint:

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- Systemic lupus erythematosus.

Although there is no cure for inflammatory arthritis, there have been many advances in treatment, particularly in the development of new medications. Early diagnosis and treatment can help patients maintain mobility and function by preventing severe damage to the joint.

-

Anatomy

The hip is a ball-and-socket joint. The socket is formed by the acetabulum, which is part of the large pelvis bone. The ball is the femoral head, which is the upper end of the femur (thighbone).

A slippery tissue called articular cartilage covers the surface of the ball and socket. It creates a smooth, low-friction surface that helps the bones glide easily across each other. The surface of the joint is covered by a thin lining called the synovium. In a healthy hip, the synovium produces a small amount of fluid that lubricates the cartilage and aids in movement.

-

Description

The most common form of arthritis in the hip is osteoarthritis — the «wear-and-tear» arthritis that damages cartilage over time, typically causing painful symptoms in people after they reach middle age. Unlike osteoarthritis, inflammatory arthritis affects people of all ages, often showing signs in early adulthood.

Rheumatoid Arthritis

In rheumatoid arthritis, the synovium thickens, swells, and produces chemical substances that attack and destroy the articular cartilage covering the bone. Rheumatoid arthritis often involves the same joint on both sides of the body, so both hips may be affected.Ankylosing Spondylitis

Ankylosing spondylitis is a chronic inflammation of the spine that most often causes lower back pain and stiffness. It may affect other joints, as well, including the hip.Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

Systemic lupus erythematosus can cause inflammation in any part of the body, and most often affects the joints, skin, and nervous system. The disease occurs in young adult women in the majority of cases.People with systemic lupus erythematosus have a higher incidence of osteonecrosis of the hip, a disease that causes bone cells to die, weakens bone structure, and leads to disabling arthritis.

-

Cause

The exact cause of inflammatory arthritis is not known, although there is evidence that genetics plays a role in the development of some forms of the disease.

-

Symptoms

Inflammatory arthritis may cause general symptoms throughout the body, such as fever, loss of appetite and fatigue. A hip affected by inflammatory arthritis will feel painful and stiff. There are other symptoms, as well:

A dull, aching pain in the groin, outer thigh, knee, or buttocks

Pain that is worse in the morning or after sitting or resting for a while, but lessens with activity

Increased pain and stiffness with vigorous activity

Pain in the joint severe enough to cause a limp or make walking difficult -

Doctor Examination

Your doctor will ask questions about your medical history and your symptoms, then conduct a physical examination and order diagnostic tests.

Physical Examination

During the physical examination, your doctor will evaluate the range of motion in your hip. Increased pain during some movements may be a sign of inflammatory arthritis. He or she will also look for a limp or other problems with your gait (the way you walk) due to stiffness of the hip.X-rays

X-rays are imaging tests that create detailed pictures of dense structures, like bone. X-rays of an arthritic hip will show whether there is any thinning or erosion in the bones, any loss of joint space, or any excess fluid in the joint.Blood Tests

Blood tests may reveal whether a rheumatoid factor—or any other antibody indicative of inflammatory arthritis—is present. -

Treatment

Although there is no cure for inflammatory arthritis, there are a number of treatment options that can help prevent joint destruction. Inflammatory arthritis is often treated by a team of healthcare professionals, including rheumatologists, physical and occupational therapists, social workers, rehabilitation specialists, and orthopaedic surgeons.

Nonsurgical Treatment

The treatment plan for managing your symptoms will depend upon your inflammatory disease. Most people find that some combination of treatment methods works best.Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Drugs like naproxen and ibuprofen may relieve pain and help reduce inflammation. NSAIDs are available in both over-the-counter and prescription forms.

Corticosteroids. Medications like prednisone are potent anti-inflammatories. They can be taken by mouth, by injection, or used as creams that are applied directly to the skin.

Disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs). These drugs act on the immune system to help slow the progression of disease. Methotrexate and sulfasalazine are commonly prescribed DMARDs.

Physical therapy. Specific exercises may help increase the range of motion in your hip and strengthen the muscles that support the joint.

In addition, regular, moderate exercise may decrease stiffness and improve endurance. Swimming is a preferred exercise for people with ankylosing spondylitis because spinal motion may be limited.

Assistive devices. Using a cane, walker, long-handled shoehorn, or reacher may make it easier for you to perform the tasks of daily living.

Surgical Treatment

If nonsurgical treatments do not sufficiently relieve your pain, your doctor may recommend surgery. The type of surgery performed depends on several factors, including:- Your age

- Condition of the hip joint

- Which disease is causing your inflammatory arthritis

- Progression of the disease

The most common surgical procedures performed for inflammatory arthritis of the hip include total hip replacement and synovectomy.

Total hip replacement. Your doctor will remove the damaged cartilage and bone, and then position new metal or plastic joint surfaces to restore the function of your hip. Total hip replacement is often recommended for patients with rheumatoid arthritis or ankylosing spondylitis to relieve pain and improve range of motion.

MORE ORTHOPEDIC MEDICAL ARTICLES